Living wasn’t always as comfortable as it is now. Back then, people didn’t have heating, air conditioning, beds, clean conditions, running water, or even their own space. Throughout history, living conditions have been difficult, dirty, and unhygienic. Many people died from the disease at a young age, and oftentimes, sewage was seen running through the streets. Clean drinking water was hard to come by, and sanitation was nonexistent. We’re going to take a look at some historic homes that were so bad, that it seems impossible that they housed people at one point in history.

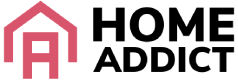

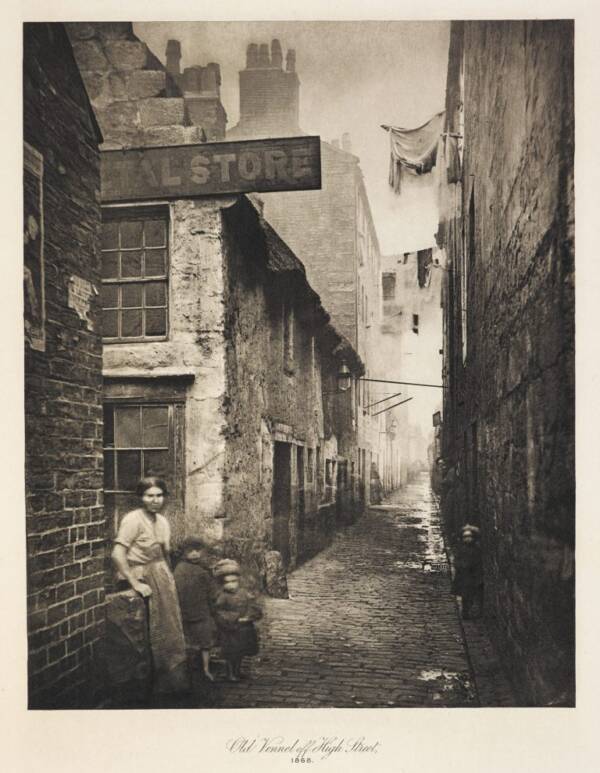

London During the Industrial Revolution

According to the Museum of London, “London’s population grew rapidly during the 19th century. This led to major problems with overcrowding and poverty. Disease and early death were common for both rich and poor people. Victorian children did not have as many toys and clothes as children do today and many of them were homemade.” Life expectancy was very short, and many people did not make it past what we would consider a young age today.

To put it simply, this was not a time you’d want to live in. Many people died from disease and illness. According to Charles Dickens’s first weekly magazine, Mary Bayly said, in a very detailed description, “There are foul ditches, open sewers, and defective drains, smelling most offensively… not a drop of clean water can be obtained – all is charged to saturation with putrescent matter. Wells have been sunk on some of the premises, but they have become, in many instances, useless, from organic matter soaking into them. In some of the wells, the water is perfectly black and fetid. The paint on the window frames has become black from the action of the sulphurated hydrogen gas. Nearly all the inhabitants look unhealthy; the women especially complain of sickness and want of appetite; their eyes are sunken, and their skin shriveled.” It’s hard to imagine people slept, ate, and worked in these conditions. At least it’s nothing like it used to be.

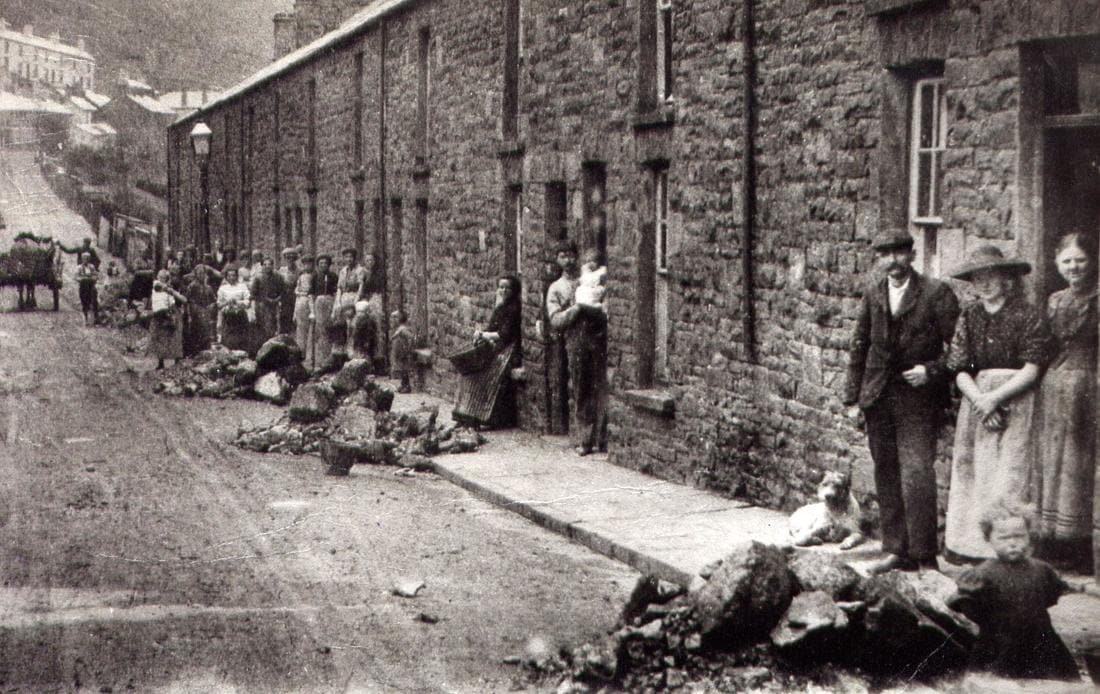

Seattle’s Dust Bowl Shantytowns (1930s)

During the Great Depression, life in the United States was rough. There was economic hardship, and most families lived in shantytowns, which were makeshift settlements with rudimentary shelters that barely protected them from the elements. These shantytowns earned the name “Hooverville,” all thanks to President Herbert Hoover who was held to be responsible for this economic crisis.

But the most noteworthy of them all was Seattle’s Hooverville, which stood from 1931 to 1941. Up to 1,200 people lived there, and they even had an unofficial mayor. Sociology student Donald Roy, who had seen this shantytown, described them as “scattered over the terrain in insane disorder.” Out of 639 residents, all but 7 of them were men, thanks to the city’s sanitation rules which required children and women not to live in Hooverville (Washington).